exposed to the atmosphere, it undergoes a physical and

chemical process called WEATHERING, which, over a

sufficient length of time, disintegrates and decomposes

the rock into a loose, incoherent mixture of gravel, sand,

and finer material.

Soil Quality

The intended use of the soil is the determining factor

in the quality required. In general, soil used for fills and

subgrades do not have to meet the same specifications

as those used for compacted rock surfaces, base courses,

or pavements.

Seven properties of rock are used to help select rock

and aggregates for construction. Briefly, these rock

properties are as follows: toughness, hardness,

durability, chemical stability, crushed shape, surface

character, and density. Toughness, hardness, and

durability are commonly checked in the field with a

simple field test.

Hardness is the resistance of a rock to scratching or

abrasion. This property is important in determining the

suitability of aggregate for construction. Hardness can

be measured using the Mob’s scale of hardness (table

5-2). The harder the material, the higher its number on

the Moh’s scale. Any material will scratch another of

Table 5-2.-MOH’S Scale of Hardness

Mineral

Hardness

Diamond . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 10

Corundum . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 9

Topaz or beryl . . . . . . . . . . . . . 8

Quartz . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 7

Feldspar . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 6

Apatite . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 5

Fluorite . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 4

Calcite . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 3

Gypsum . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 2

Talc . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 1

Expedients

Porcelain . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 7.0

Steel file . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 6.5

Windowglass . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 5.5

Knife blade . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 5.0

Copper coin . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 3.0

Fingernail . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 2.0

equal or lesser hardness. In the field, hardness may be

measured using the common expedients shown in table

5-2; for example, when you are able to scratch a rock

with a knife blade, the rock has a hardness of 5.0 or less.

A rock which can be scratched by a copper coin has a

hardness of 3.0 or less.

Aggregates for general construction should have a

hardness of 5 to 7 and should be difficult or impossible

to scratch with a knife. Material with a hardness greater

than 7 should be avoided since they cause excessive

wear to crushers, screens, and drilling equipment.

Material with a hardness of less than 5 may be used if

other sources of aggregate prove uneconomical.

The requirements as to toughness, durability,

crushed shape, and other properties vary according to

the type of construction. Chemical stability has specific

importance when considering aggregates for concrete.

Several rock types contain impure forms of silica that

reacts with alkalies in cement. This reaction forms a gel

that absorbs water and expands to crack or disintegrate

hardened concrete. These reactive materials may be

included in some gravel deposits as pebbles or as

coatings on gravel. Potential alkali-aggregate reactions

may be anticipated in the field by identifying the rock

and comparing it to known reactive types or by

investigating structures in which the aggregate has been

used. Generally, light-colored or glassy volcanic rocks,

chert, flints, and clayey rocks should be considered

reactive unless proven otherwise.

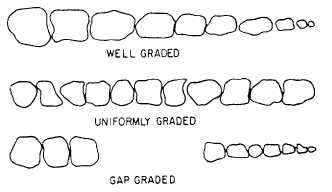

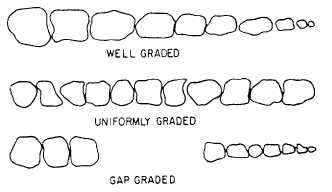

An additional property of rock is gradation (fig.

5-1). This property is also important for evaluating rock

as possible construction material. Gradation is the

distribution and range of particle sizes that are present

in, or can be obtained from, a deposit. The gradation of

pit materials can be readily determined from a simple

test. Quarry materials may be more difficult to evaluate.

Figure 5-1.-Types of soil gradation.

5-3